From atmospheric tornadoes to quantum condensates and aircraft wakes, vortices are a universal form of organization in fluids. Any rotating flow naturally structures itself into filamentary objects known as vortices.

Along these vortices propagate a particular class of waves known as Kelvin waves, which play a key role in vortex stability and in the transport of energy within the fluid. First described theoretically by Lord Kelvin at the end of the 19th century, they are considered the most fundamental excitations of a vortex. Yet, despite their central importance in fluid mechanics, their dynamical properties had never been measured directly and quantitatively in a controlled experiment.

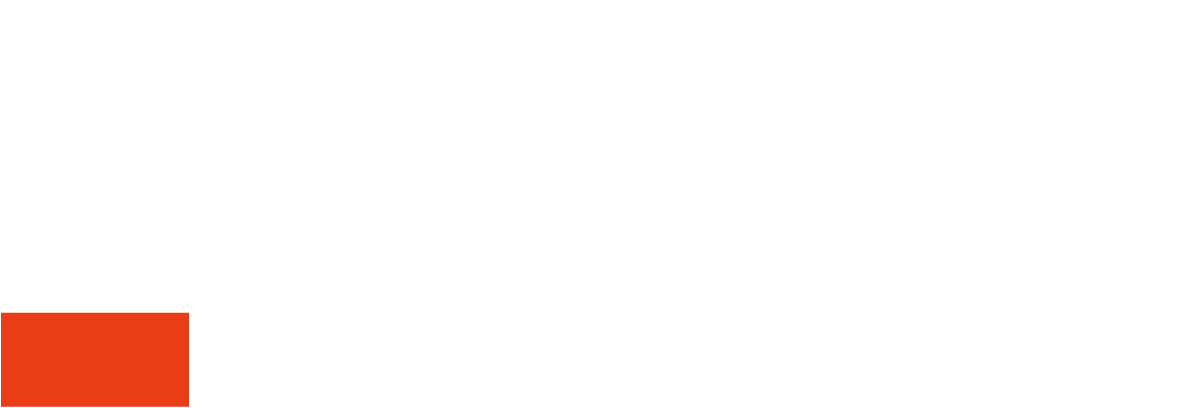

Researchers from the Laboratoire Matière et Systèmes Complexes (MSC) at Université Paris Cité, together with the Laboratoire de Physique of École normale supérieure (LPENS), have designed an experiment that recreates in the laboratory a water vortex containing an air core, similar to the one formed when a bathtub drains. This vortex forms a remarkably stable water column about forty centimeters high, pierced by a thin air filament only a few millimeters thick. This configuration provides a direct and precise visualization of vortex deformations and of the waves that propagate along it when the vortex is excited.

Using high-resolution spatio-temporal measurements, the researchers obtained the first complete experimental characterization of the dispersion relation of Kelvin waves. This relation, which links the wavelength of a perturbation to its propagation speed, constitutes the dynamical fingerprint of the waves and reveals how energy is transported along a vortex. The results, published in Nature Physics, show striking agreement with theoretical predictions established more than a century ago and reveal the existence of several distinct types of Kelvin waves with different dynamical behaviors.

These findings have implications across a wide range of fields. Rotating quantum fluids, such as liquid helium or Bose–Einstein condensates, are dominated by extremely thin vortices while exhibiting no classical energy dissipation. Kelvin waves play a central role in these systems, and their dispersion relation is theoretically identical to that measured in the present experiment. The results therefore provide a relevant macroscopic analogue of quantum systems and offer new insight into the mechanisms of energy transfer in quantum fluids.

In geophysics, this study sheds new light on tornado dynamics. It shows that the propagation of certain types of Kelvin waves can lead to a local concentration of energy within the vortex. This mechanism may provide a simple explanation for the so-called skipping effect, characterized by phases during which a tornado lifts off the ground and subsequently reattaches. The intermittent nature of Kelvin waves may also help explain some of the abrupt lateral displacements observed in these phenomena.

Experimental setup for the observation of Kelvin waves.

The transparent cylinder is filled with water and contains a thin air core at its center, formed by a draining vortex. The sinusoidal deformations visible along the air core correspond to Kelvin waves propagating along the vortex axis. At the bottom of the figure (in red), the water injection and drainage system is shown; it is used to generate and control the draining vortex.

More:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-026-03175-w

Affiliation author:

Laboratoire de physique de L’École normale supérieure (LPENS, ENS Paris/CNRS/Sorbonne Université/Université de Paris)

Corresponding author: Christophe Gissinger

Communication contact: L’équipe de communication